Marc Humbert, Emeritus Professor of political economy at University of Rennes, Liris, Franceonomy at University of Rennes, Liris, France. [1]

My presentation is divided into four parts. I will first recall the context which led to the second convivialist manifesto, then I will sketch the evolution of the world between the two publications, Tools for conviviality in 1973 and the Second Manifesto in 2020. I will present in part III, Illich’s book as a Critical Theory and I will finally link all that to the Convivialism’s principles.

I – The general context for a convivialist manifesto

The 2nd convivialist Manifesto has been co-signed by nearly 300 intellectuals, i.e. distinguished scholars who are sociologists, economists, political scientists, philosophers etc. as well as community activists, renowned essayists, from 33 different countries. They form a kind of informal “convivialist international” that you are invited to join. The text of this 2nd Manifesto is already available in English, German, Italian, and soon in Spanish and in Portuguese.

The idea to design a kind of societal philosophy called “Convivialism” was born in Tokyo, ten years ago, in July 2010, during a symposium organized at the French-Japanese-House, Nichifutsukaikan, with colleagues, Japanese, French, German, Italian. Among them my friend the late Prof Nishikawa Jun who was emeritus at Waseda and who was active in the Global Asia Research Center. Our objective was to discuss the possibility to have societies which would work in targeting a good life for all and not in search of maximizing the growth of their GDP.

Observing the state of the world at that time, in 2010, we were convinced that there should be something wrong in the very many ideas and in the millions of concrete actions that had come up at least since the 1970s in the global scene, claiming that another world is possible. Clearly, they had flourished in vain. The least we could say, was that, 40 years later, this new world was still to come. Maybe that all these attempts must be taken into consideration, but they were not sufficient. It certainly lacked something to make them able to change the curse of things. What? It seemed to us that the key element missing was to base ideas and actions on a radically new analysis, starting from new premises.

However, Illich’s Critical Theory brought the base for such a necessary new analysis. But it had not be used. We drew upon it, up to a certain extent, and we decided to design a new societal philosophy and to word it “convivialism.” And to disseminate these ideas, as widely as possible, through a Manifesto. We try to provoke a decisive shift in the way of thinking of a majority of the world population. We are convinced that this is a necessary condition to curb the path along which our humanity is driven. A path that could lead to chaos as the historical, terrific, ongoing evolution seems inescapable.

Our attempt to design a radically new societal philosophy does not mean to make a clean sweep of all the old “doctrines and wisdoms that were handed down to us “[… but] to retain the most precious principles enshrined [ in them],”[2] those principles which are precious because they may contribute to a “good life” for all. This does not mean an elaboration of a kind of synthesis of past or present ideologies as socialism, communism, anarchism, liberalism or “ecologism.” Clearly, we may say that convivialism “is located beyond the marked trails,” to echo the warning of Esprit about Illich’s stance,[3] it cannot be classified “into ready-made categories: left, right, progressive, reactionary.” To build a better future it is necessary to get rid of their insufficiencies and their oppositions which have built our present terrific situation. We have to transcend[4] them, making an “Aufhebung” in the sense of this German word, used by Hegel and Marx.

To give a chance to these new basic ideas to provoke the necessary radical change, it is necessary to convince a majority of people by a logically coherent analysis explained in ordinary language, as simply as possible. This is a huge challenge. People need an attractive and guiding project for the future, to help them dream, imagine, a convivial society; a kind of utopia for the 21st century.

II – The state of the world (1973 – 2020)

Illich observes – in 1973- that the process of society has been reduced to an “increasing demand for products”[5] and that in response, the whole humanity seems to be devoted to the growth of its GDP.

As a matter of fact, since the 1970s, despite general aspiration for growth, the pace of growth has significantly slowed everywhere – except in China and in a few dynamic emerging economies, principally located in Asia. Nevertheless, the whole working of societies, almost everywhere in the globe, is subjected to the objective the GDP growth, to fulfill an ever-increasing demand for products and services.

However, the working of societies and what is delivered to people generate growing frustration among the majority of the world population and they are no longer confident in the existing world socio economic order to get them what they want.

The distrusted socioeconomic order is clearly dominated by capitalism (either in Western “liberal” democracies or in China, a communist popular democracy). Capitalism was born a long time ago and since that, Capitalism has evolved a lot. The present dominant form of capitalism is sometimes said- as in the Manifesto- a capitalism “rentier and speculative.”[6] However, avoiding the strong connotation of the word capitalism, general opinion prefers the qualification of the present socio-economic order as “neoliberalism.” More and more people disagree to support this neoliberal order. Some feel lost and fold in on themselves and their community, other are tempted by one of the following three options: to end with capitalism, to get rid of growth, to seek a savior.

(i) Let’s end with capitalism and capitalist economy.

The temptation to reject totally capitalism concerns few people. Their dreams have been drowned with the collapse of USSR in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall. No more central planning systems. Even a mix of “State and Market” was no longer relevant since Western countries had turned, after 1979, under the leadership of Ms Thatcher, from welfare state to privatization, deregulation, globalization and new public management. States had been supposed to master the markets, but finally markets have changed the States.

If anti-capitalism option seems now almost impossible, a combination of capitalism with other forms of economy gathers, at least in concrete activities, people in an ever-increasing number. It was first called social economy organized by cooperatives. Since the 1970s its dynamism lies principally in “popular or solidarity economy.” There are promoters of that everywhere in the world. However, one of his French promoters, Jean-Louis Laville, recalled a Latin American author who has said: “we thought that cooperatives would change the market, but finally the market changed the cooperatives.” Thus, solidarity economy is important but within an unchanged system, it is in danger. This is exemplified by the rise of so-called social business.

(ii) Let’s get rid of growth.

There is an important movement of intellectual and activists in favor of de-growth, mainly in old industrialized countries. It hurts frontally the expectations for more consumption that are very high within the majority of the people everywhere in the world. Nevertheless, the promotion of sobriety, of a frugal or responsible consumption to save the planet meets a broad audience, larger and larger as the ecological issue is felt stronger. However, the growth optimizing bureaucrats and experts keep the lead, delivering the illusion of a possible “green growth.” Green capitalism is capturing the support of the population aware of the ecological threat but which is addicted to consumption and growth.

(iii) Let’s seek a savior

A significant part of the world population turns to populism or to religious beliefs to secure their lives and their souls which they put into the hands of a savior.

III – Illich’s critical theory

A lot of initiatives and projects have been set up, to respond to people’s dissatisfaction. They are inefficient as they are fighting the symptoms without having first properly diagnosed the disease. It is necessary to point out what is the social pathology to deal with. Let us see what this pathology according to Illich is.

For him, society is suffering from crimes perpetrated directly and indirectly by the industrial regime. These are the excessive overstepping of limits and scales and the acceleration of the pace of change. And this could upset what are the foundations of our humanity.

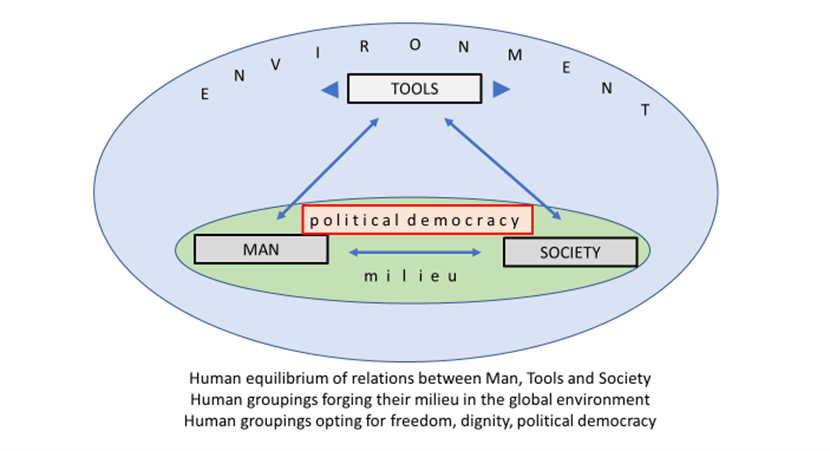

Illich’s critical theory focuses on the importance “to articulate the triadic relationship”[7] between Man, Tools and Society[8] that should “be kept in equilibrium to maintain the homeostasis which constitutes human life.”[9]

I have tried to translate into a diagram his argument explaining what is human life all about.

Tools – Environment

The definition of “tools” is extensive: it refers to two main categories: technical tools (“physical machines”) as knives or cars, and bureaucratic or institutional tools (“social arrangements”) as the education system or the Legal procedure; all of them have been forged by Man and Society for their use. A third important category is a little difficult to apprehend. According to Illich, tools must respect the “balance between man and the biosphere”[10] so that “the use of nature does not make nature useless for man.”[11] This last quotation makes clear that according to Illich, Man uses nature, which means that nature, or at least elements of nature, are considered as tools by Man, by society, a resource to sustain life and the human equilibrium.

Society- Milieu – Democracy

Human beings are co-building themselves in relationship with others, and firstly in relation with their parents or other caregivers, partly through tools as language and symbols. Building altogether a society, as other social species do. Moreover, they are not living in an abstract realm or a desert, they are installed on the ground, within a limited piece of earth to share as it is and with other species, known or unknown, visible or not. Each human grouping lives in a specific place-, this is its “milieu”[12] as a piece of socialized nature. They have a common perception of it, and they use it (as a tool then) according to their customs and first to build themselves, to feed themselves, to forge other tools. All these characteristics are specific to a certain grouping of human beings, at a certain moment in time.

Beyond that anthropological statement, Illich stands for a societal characteristic which has appeared in European societies in the aftermath of the Enlightenment. Illich values “individual freedom realized in personal interdependence [which is …] as such an intrinsic ethical value.”[13] So that, when new born human beings are educated and are knowing enough, they take full place in the life of society, as “politically interrelated individuals.”[14] Illich clearly states that this leads to a “conscious use of disciplined procedure that recognizes the legitimacy of conflicting interests […] and the necessity of abiding by the decision of peers.”[15] In other words, a society would set up a political democracy between equals, with a commonly accepted law, which is a tool for a good society.

Overstepping of limits or self-limitation of scales and pace of change

To Illich, the key observations to assess the social pathology are these of the relations of man to his tools and the impact on the multidimensional balance of human life in society. According to him, it is “necessary to recognize natural scales and limits [16] […] “tools that require time periods or space or energies much beyond the order of corresponding natural scales are dysfunctional. They upset the homeostasis”[17] “which constitutes human life.”[18] He insists that when it grows beyond a certain point on this scale […a tool] becomes a threat to society itself.”[19]

Thus, the culprit is not exactly the tool by itself. In human history, in a society history, when a new tool has been forged, at the beginning, it is adapted to the human life, to society and it serves it. Dysfunctionality occurs with the overshot. He gives as an example the fact that, “it has taken almost a century to pass from an era served by motorized vehicles to the era in which society has been reduced to virtual enslavement to the car.”[20] Thus, there is no hostility to innovation and technical change.

Illich states that “The human equilibrium is open. It is capable of shifting within flexible but finite parameters. People can change, but only within bounds.”[21] For him, the main reason which “imposes limits to the change of tools [… is] Man’s need for language and law, for memories and myths […thus,] “an increase in the rate of innovation is of value only when with it, rootedness in tradition, fullness of meaning, and security are also strengthened.”[22]

Thus, in addition to the excess size that the tools reach, dysfunctionality comes from the pace of change, either the pace of change from one tool to a replacing one, or that of the evolution or/and transformation of the same tool. According to Illich, it is an essential defect of the industrial system to be “dynamically unstable […] organized for indefinite expansion[23] […] Accelerating change has become […] intolerable […] at this point the balance among stability, change and tradition has been upset.”[24] We may note that this diagnosis is somehow the basis of the one expressed recently by the German sociologist Harmut Rosa who has pointed out that the obstacle for us, humans, to have a good life, is a social acceleration governed by the rule and logic of an acceleration-process which is indiscernibly linked to the concept and essence of modernity.[25]

Conditions for a Convivial Reconstruction

Having diagnosed the roots of the pathology of our societies, Illich enunciates three conditions to fulfil in order to avoid the main misdeeds of this industrial regime and to overcome the disease. They aimed at stopping the overshooting of limits in scale and in pace of change and to adopt a convivial stance.[26] Let us quote his own words.

(i) “The only response to this crisis is a full recognition of its depth and an acceptance of inevitable self-limitations”[27] that means “to set up, by a political agreement, a self-limitation.”[28]

(ii) “The only solution […]is the shared insight of people that they would be happier if they could work together and care for each other.”[29] This defines a society which is the opposite of “an efficiency-oriented society.”[30] Care is opposed to negative competition which is in the present industrial regime the base of education[31] and the rule of relations between firms and between nations.[32]

(iii) “The possibility of a convivial society depends […] on a new consensus about time destructiveness of imperialism on three levels: the pernicious spread of one nation beyond its boundaries; the omnipresent influence of multinational corporations; and the mushrooming of professional monopolies over production.”[33]

Six concrete misdeeds to fight

Illich analyses six concrete misdeeds – which are still threatening to get a greater negative impact on the lives of individuals and society- accomplished by industrial development since 1955 when it has globally reached an excessive scale.[34] They are presented separately, but in showing that their workings are intertwined. This does not add to the framework of analysis, but may help to strengthen its understanding.

(i) Environmental degradation to the point that it can be rendered uninhabitable.

(ii) Radical monopoly of more and more products leads to negative returns as for example Cars “ruling out locomotion on foot or by bicycle in Los Angeles.”[35] This goes so far as man and political discussion are expelled by experts and even “soon the computer will be used to define […] what should be done for the growth of tools.”[36] Today we would mention Artificial Intelligence and algorithms.

(iii) Overprogramming of people who “are constantly taught, socialized, normalized, tested and reformed”[37] at the expense of their creativity.

(iv) Polarization of power concentration in a few hands can lead “society into irreversible structural despotism”;[38] although “poverty levels rise […] the gap between rich and poor widens.”[39]

(v) Large scale obsolescence that produces devaluation of still efficient tools, but exercising a radical monopoly. Obsolescence which is provoked by “a few corporate obsolescence centers of decision-making [that] impose compulsory innovation on the entire society.”[40]

(vi) Pervasive frustration by means of compulsory but engineered satisfaction: people are addicted to growth. As any addicts they “pay increasing amounts for declining satisfactions [and] they are blind to deeper frustration.”[41]

IV – Convivialism’s principles

As I wrote earlier, after a symposium held in 2010 in Tokyo, we decided with a few colleagues, drawing upon the idea of conviviality by Illich, to search for a new base on which to have the society organized. To find renewed founding principles, let’s say a doctrinal base for a societal philosophy we would name “convivialism”. The purpose was to deliver a kind of guide to build a “convivial society”.

Following this symposium, Alain Caillé invited to discuss the project, a few dozens of intellectuals who met several times a year in Paris, and finally co-signed a first Manifesto in 2013.

It is a little book that does not aim to look as a complete or/and a scientific opus. There are in it a whole lot of assertions and reasonings which are not supported by precise quotations of authors, philosophers or sociologists, there are almost no footnotes and no references. It is written as an essay for the general public in which to show, using common sense arguments and known objective facts, what are, in the present world’s situation, the right questions to ask and to answer, to set up a good society. And we propose what seems to us the conditions to succeed in such an attempt: to respect simultaneously a few essential principles.

After the publication, we went on working to convince other intellectuals around the world, and in discussion with them, to improve the presentation of the surroundings of these principles.

This broad debate led to add a fifth principle and to make explicit a meta-principle in the Second Manifesto published in 2020 and cosigned by 276 authors from 33 countries which form the nucleus of a possible future international convivialist.

The core of the manifesto lies in a set of principles, which are the following. To my understanding the first three are founded on scientific, anthropological knowledge. However, despite the scientific base of these principles, many individuals and many human groupings decline to respect them and to act according to them. The last three rely on an ethical and political choice, that of democracy. Therefore, the whole set of principles complies with this ideal.

(i) Principle of common naturality

We must recognize that we come from the first living organisms born on Earth, that Nature immerses us as much as it surrounds us. We live in a permanent and intimate interdependence with everything that constitutes this universe. This principle breaks with the Western stance to consider human beings as subjects, and Nature as object of which they should become “masters and possessors.” Instead we state that recognizing our real place in the universe requires us to take care of Nature, and, for many in the West, to reconsider their relationships with animals.

(ii) Principle of common humanity

“Beyond differences of skin, nationality, language, culture, religion or wealth, sex or gender, there exists only one humanity, which must be respected in the person of each of its members” whatever this person’s singularity is. There is already an agreement on this, adopted by the so-called international communities of nation, it is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. However, this agreement is often flouted.

(iii) Principle of common sociality

Life is given to each of us during a biological process. But once born, we cannot continue to live without a constant inter-course with our parents and caregivers. We are a social species, and at the beginning or our common history was a society that educates and shapes us in a specific culture, in a specific milieu, which is politically organized, and where we may have a place, a role. We are living in social groups of different sizes and structures, in families, associations for various common purposes, villages, nations within which we collectively take care of each other, where we may say “we.”

(iv) Principle of legitimate individuation

The ideal of democracy shapes societies where individuals are equals in rights so that they are all accompanied by society to enable them to express their individuality to the fullest, by developing their capabilities and their power to be and to act. It means individual freedom and a limit to social control that must not be totalitarian. Simultaneously, individual empowerment must not be illimited, otherwise, society would be deleted. Instead of society, we would have a set of free individuals fighting against each other, to assert themselves.

(v) Principle of creative opposition

Democracy organizes the interdependence of free individuals with equal rights. Between them rivalry and oppositions, conflicting interests must be recognized as legitimate as far as they are non-violent and not destructive.[42] Deliberative processes, guided by legal procedure set up by a collective agreement, have to turn oppositions into a creative source of contributions to the common good.

(vi) Imperative of hubris control

It is in human nature to be tempted by omnipotence, excessiveness, temptation of always more. Thus, it would be impossible to enforce any of the preceding principles, which are interdependent, without an agreement of all, for individual and collective self-limitation.

And then?

This set of principles is a guide to assess whether a certain state of the world is convivial or not. It says nothing about the processes through which they could be implemented in the present world and about how to make it shift towards a better one.

The second Manifesto expresses in its conclusion that to embark on policies aiming at such a radical change of the world is very risky:

“The task is difficult and dangerous. We don’t deny the fact that on the road to success, we will be facing, and we will have to surmount, formidable powers – financial, material, technical, scientific, and intellectual, as well as military and criminal.”[43] And the Manifesto indicates that as weapons to fight, we have only two: the indignation in the world population which is growing and the hope that sooner or later the indignant recognize themselves in accordance with the principles of convivialism, so that their indignation can turn into a force for change. Such a wide recognition will be an opportunity for a convergence of all the forms of resistance, and resilience already active at countries and international levels. Then, a convivial world will be in sight.

A few proposed policies[44]

Thus, the second Manifesto does not claim to present a set of policy measures which would form a kind of political program to establish a convivial society. It simply lists ideas of policies aimed at correcting a few misdeeds of the present “neoliberal” order. One point in discussion is whether it could be possible to find a small set of tilting measures that would chain the others and bring about the expected radical change what individual, even numerous measures cannot bring.

Hereafter we have the principal measures listed in the Manifesto and considered as correcting some defects in the present working of our world.

There are proposals aimed at restoring activities to the service of society’s objective: conviviality, individual and collective emancipation. Production activities must meet the real needs of society and not create fictitious ones, which is what the present order leads to, as it is subjected to rentier and speculative capitalism. This requires strict regulation of finance, removal of tax havens, limiting the size of banks, etc. Since the essential objective is to give all human beings access to a dignified life, the criterion of effectiveness will no longer be that of increasing GDP. We must enter an era of post-growth compatible with the maintenance of the planet’s habitability and the practice of unconditional attention to all those – discriminated economically and/or culturally – who must be supported by an interdependence that leads them towards emancipation. The second Manifesto highlights in particular the need to renew gender relations.

The de-financialization and re-embedding of the economy in the service of society must be accompanied by restructuring measures. Reversing the trend towards generalized commodification by extending the field of the non-market exchanges: exchanges of services between citizens, between relatives, short circuits, collaborative economy, free public services, circular economy, advertising regulation, time management, reinvention of “work”. To leave only what can be left to the markets and to monitor their “convivial” functioning. Reversing the trend towards globalization and hyper-concentration by relocating activities, creating complementary local currencies, restoring food and industrial sovereignty, favoring small structures and practicing the negotiated management of international trade, reducing it to what is necessary to meet real needs.

Finally, there must be measures to regain democratic control on the techno-scientific evolution, which is now being hit hard by the hubris and the temptation of omnipotence, in order to make it ethically and socially beneficial. This requires the dismantling of the giant firms that impose on us technological advances in their own benefit, alienating the populations.

_____________________________________________________

[1] Paper presented at the Waseda University’s Global Asia Research Center Special Seminar, Tokyo, 2020, October, 26

[2] In this piece, if no other indication, I quote the Second Manifesto in the text that has been published by the review Civic Sociology, in its June 2020 issue (International Convivialist (2020) “THE SECOND CONVIVIALIST MANIFESTO: Towards a Post-Neoliberal World” Civic Sociology, June, p.1 – 24, https://online.ucpress.edu/cs/article/1/1/12721/112920/THE-SECOND-CONVIVIALIST-MANIFESTO-Towards-a-Post, here, p. 7.

[3] “Do not try to classify this thought into ready-made categories: left, right, progressive, reactionary. Its first interest is precisely […] to be located beyond the marked trails,” Esprit, March 1972, p. 322.

[4] Civic Sociology, p.7.

[5] Ivan Illich (1973) Tools for Conviviality, London, Marion Boyars, p. 11.

[6] Civic Sociology, p. 2.

[7] Tools for Conviviality, p. x.

[8] The text here (p. x) reads “between persons, tools and a new collectivity.” In trying to formalize the critical theory of Illich, and to make it clearer, I have standardized here (and in other places) the wording, keeping the spirit and the line of reasoning of Illich.

[9] Tools for Conviviality, p. 84.

[10] Tools for Conviviality, p. 48.

[11] Tools for Conviviality, p. 84.

[12] This anthropological stance is coherent with Illich’s thought but he does not express it like that, and he does not use the word “milieu” in the precise sense that I borrow from Augustin Berque (2001) Écoumène. Introduction à l’étude des milieux humains, 2001, Paris, Belin. Berque has built “mesology – the science of ‘milieux'” upon the complementary works of two authors. First, the German Naturalist Jakob von Uexküll who distinguished (1934) Umwelt (a concrete surrounding with which a given Human grouping is concerned) and Umgebung (the raw data of the universe, the global environment, as a concept and as an object of scientific study). Second, the Japanese philosopher, Watsuji Tetsurô (1935). He distinguished from the “scientific environment” called in Japanese shizen kankyô 自然環境), fûdo 風土 , the “milieu,” where, explains Berque, “the social dimension is as much important as the data of the physical environment” (qu’est-ce que la mésologie ? pour sciences critiques http://ecoumene.blogspot.com/2018/02/au-est-ce-que-la-mesologie-Berque-Moreau.html ).

[13] Tools for Conviviality, p.10.

[14] Tools for Conviviality, p. x.

[15] Tools for Conviviality, p. 106.

[16] Tools for Conviviality, p. xii.

[17] Tools for Conviviality, p. 78.

[18] Tools for Conviviality, p. 84.

[19] Tools for Conviviality, p. x.

[20] Tools for Conviviality, p. 7.

[21] Tools for Conviviality, p. 46.

[22] Tools for Conviviality, p. 84.

[23] Tools for Conviviality, p. 46.

[24] Tools for Conviviality, p. 75.

[25] Harmut Rosa (2010) Alienation and Acceleration – Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality, København, NSU Press. Rosa’s “alienation” is close to Illich’s “enslavement.” Both quote the famous aphorism by Benjamin Franklin (1748, Advice to a Young Tradesman) “Time is money” (Illich, p 31. Rosa, p.26).

[26] Again, we may see a proximity with Harmut Rosa, if we read what Residenz Verlag wrote to present his last book (Harmut Rosa (2018) Unverfügbarkeit [unavaibility],Salzburg, Residenz Verlag): “Ein fundiertes Plädoyer für eine Gesellschaft die der Welt Grenzen sitzt” [A sound plea for a society that sets limits to the availability of the world –my translation].

[27] Tools for Conviviality, p. 107.

[28] My translation of a precision given by Illich in the French edition: Ivan Illich (1973) La convivialité, Paris, Le Seuil, p. 153.

[29] Tools for Conviviality, p. 50.

[30] Tools for Conviviality, p. 38. This point against the harsher and harsher pressure for competitive profitable efficiency, everywhere, in social arrangements, in administrations and within firms was recently adopted by Albena Azmanova. With it she underlines that it is not Capitalism per se which we should fight but this posture that leads to precarity, see: Albena Azmanova (2020) Capitalism on Edge. How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia, New York, Columbia University Press.

[31] “Age-specific, compulsory competition on an unending ladder for lifelong privileges cannot increase equality but must favor those who start earlier, or who are healthier, or who are better equipped outside the classroom. Inevitably, it organizes society into many layers of failure, with each layer inhabited by dropouts schooled to believe that those who have consumed more education deserve more privilege because they are more valuable assets to society as a whole”. Tools for Conviviality, p.41.

[32] “this [industrial] race takes the form of a competition among multinational corporations and industrializing nation-states”, Tools for Conviviality, p. 88-89.

[33] Tools for Conviviality, p. 43.

[34] Tools for Conviviality, p. 47 sqq. According to Illich, two watersheds divide the evolution of the industrial regime, the first in 1913 and the second in 1955. The last opens a period which is almost that Rosa (op.cit.) calls late modernity.

[35] Tools for Conviviality, p. 52.

[36] Tools for Conviviality, p. 93

[37] Tools for Conviviality, p. 76.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Tools for Conviviality, p. 69.

[40] Tools for Conviviality, p. 73.

[41] Tools for Conviviality, p. 82.

[42] Humanity, sociality, and individuation, even hubris are usual concepts in the literature, however, that of “creative opposition” is less common. It is associated in the Manifesto with the mention that to deal with the mother of all threats it would be necessary “to encourage people to cooperate by giving their best while allowing them to oppose without killing each other“(quotation from the Chap.1 “The Core Challenge” of the Second Manifesto, not translated in Civic Sociology, located p.36 in the French text). This special wording of the democratic principle is a formula exhibited by Alain Caillé during our discussions to insert a tacit reference to The Gift from Marcel Mauss (Marcel Mauss (1950) Essai sur le don, Paris, PUF [1924]). There, Mauss concluded (op.cit., p. 278, followed by the English version, according to Marcel Mauss (1990) The Gift, London, Routledge, p.106) : “dans notre monde dit civilisé, les classes et les nations et aussi les individus, doivent savoir – s’opposer sans se massacrer et se donner sans se sacrifier les uns aux autres.” The English translation is slightly different: “peoples have learnt how to oppose and to give to one another without sacrificing themselves to one another. This is what tomorrow, in our so-called civilized world, classes and nations and individuals also, must learn.” With the English translation, it seems that learning is necessary, and that we have to wait until tomorrow.

[43] Civic Sociology, p. 13.

[44] These propositions are listed in chapter VI. Civic Sociology does not provide a translation for this chapter.